-

![Trumbull's painting of Declaration of Independence signing]()

The Declaration of Independence - 1776

The Declaration of Independence served a single, decisive purpose: to sever political ties with Great Britain. It was a statement of intent, not a framework for governance. While it proclaimed that "all men are created equal," this principle was inconsistently applied, revealing the deep-seated contradictions of the era. In short, ‘men’ did not include women or slaves.

This distinction is crucial for modern understanding. Many of us, incorrectly, cite the Declaration's philosophical or religious language—it references God four times—as the foundation of U.S. law. However, legal and governmental authority rests solely in the Constitution, a secular document that establishes our form of government without any mention of a deity. Mistaking one for the other fundamentally misrepresents the sources of our ideals versus our laws.

-

![Painting of Articles of Confederation signing]()

The Articles of Confederation - 1781

The Articles of Confederation served as the first constitution of the United States. Drafted from a fear of centralized authority, it created an intentionally weak national government and a loose "league of friendship" among sovereign states.

The Confederation Congress lacked crucial powers: it could not levy taxes, regulate interstate commerce, or effectively raise a national army. Each state had a single vote, and significant legislation required a supermajority, while amendments required unanimous consent, making governance difficult and inefficient.

This structure led to economic instability, inability to pay war debts, and internal conflicts. The manifest failures of the Articles prompted leaders to convene the Constitutional Convention in 1787, ultimately replacing them with the current U.S. Constitution.

-

![Constitution Document over flag]()

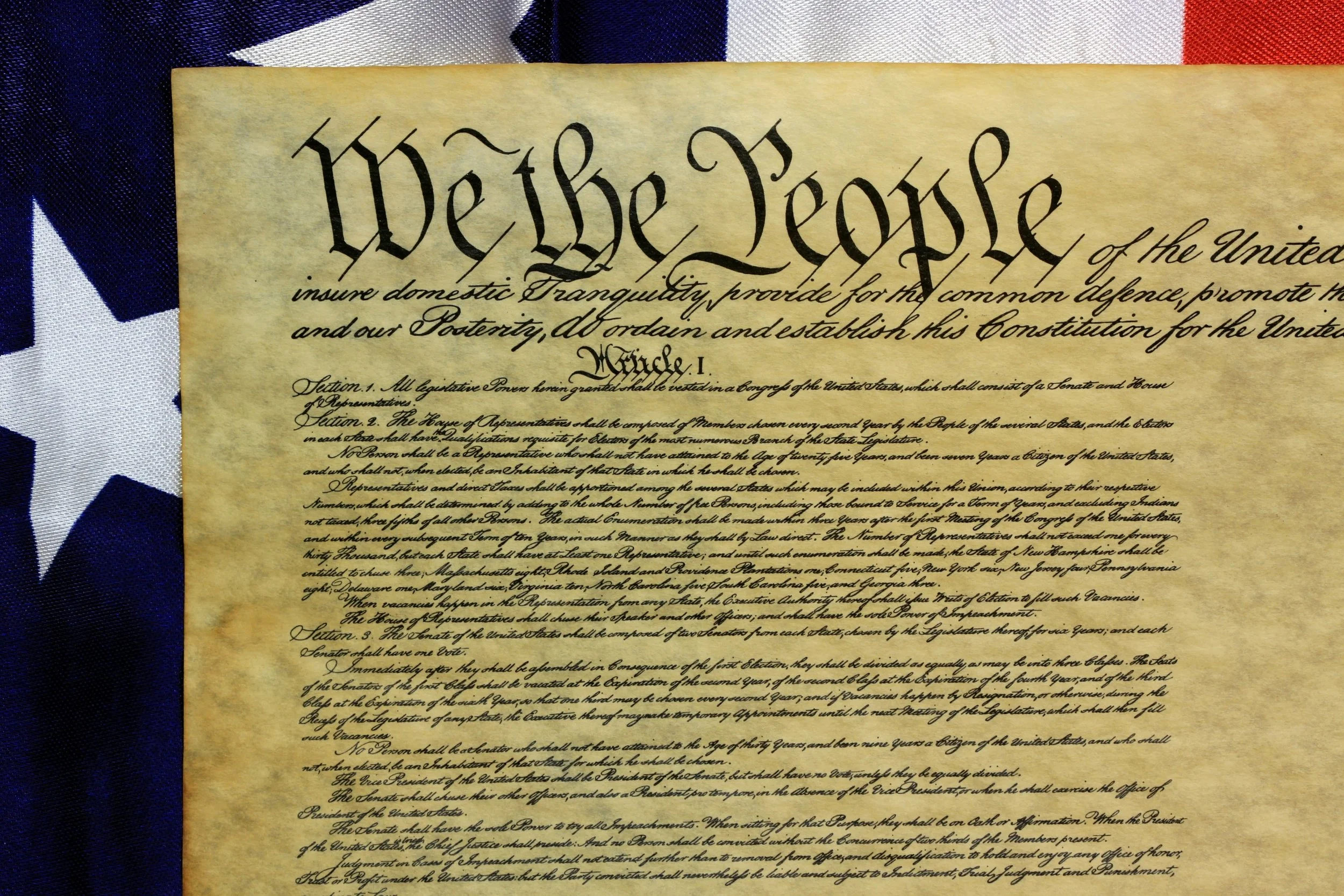

The Constitution - 1788

The United States Constitution is a revolutionary document that provided an ingenious blueprint for a stable and adaptable democratic republic. Its primary achievement was the creation of a durable government framework designed to protect liberty.

It masterfully accomplishes this by distributing power among three co-equal branches—the legislative, executive, and judicial. The Legislative Branch (which comes first in the Constitution) is comprised of Congress (the House of Representatives and the Senate). The Executive Branch (second in the Constitution) is the Office of the President). The Judicial Branch (third in the Constitution) is comprised of the Supreme Court and the system of Federal Judges. This structure, governed by an intricate system of checks and balances, attempts to prevent any single branch of the government from becoming too powerful. Furthermore, the principle of federalism establishes a dynamic balance between a strong national authority and the rights of individual states.

Forging this union required navigating immense challenges. To unite states with vastly different interests, pragmatic but deeply painful compromises were made, such as the Three-Fifths Compromise regarding slavery. Similarly, widespread fear of a new central power was resolved only by the crucial promise to add amendments protecting individual rights at a later date. The Constitution’s ultimate triumph lies not in being perfect from the start, but in its resilience, creating a government strong enough to last yet flexible enough to evolve toward a "more perfect Union."

-

![Modern bill of rights on top of flag]()

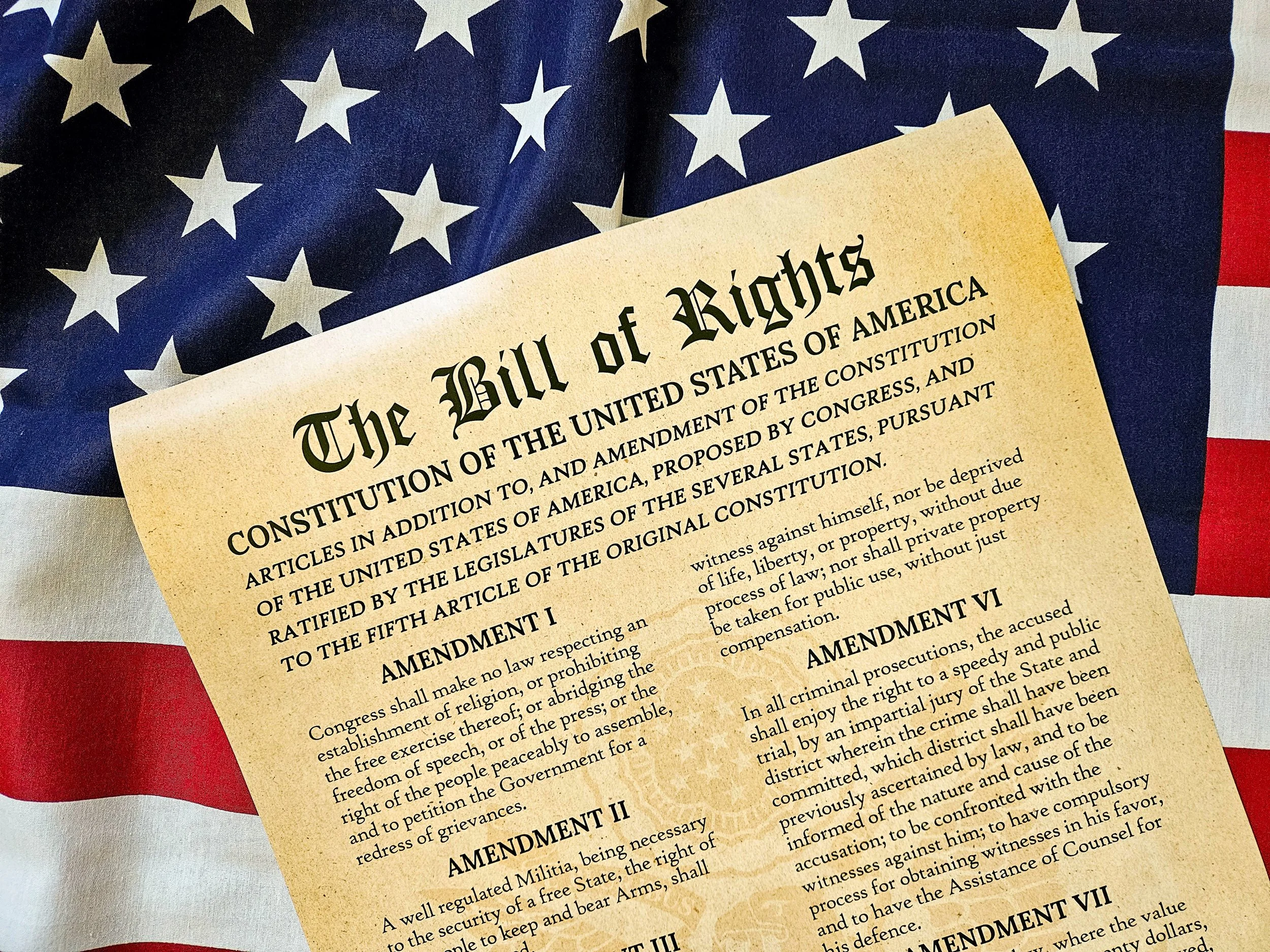

The Bill of Rights - 1791

The Bill of Rights consists of the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was added to address the fierce objections of Anti-Federalists who feared the new national government would infringe upon individual liberties.

Championed by James Madison, these amendments serve as a foundational charter of American freedom, placing explicit limits on governmental power. They guarantee essential rights such as freedom of speech, religion, and the press (First Amendment); the right to bear arms (Second Amendment); and protections for those accused of crimes, including the right to a fair trial and due process (Fourth through Eighth Amendments).

Crucially, the Bill of Rights concludes by reserving all powers not specifically granted to the federal government to the states or the people, thereby cementing its role as the cornerstone of American civil liberties.

-

![Listing of 9 of the last 16 constitutional amendments]()

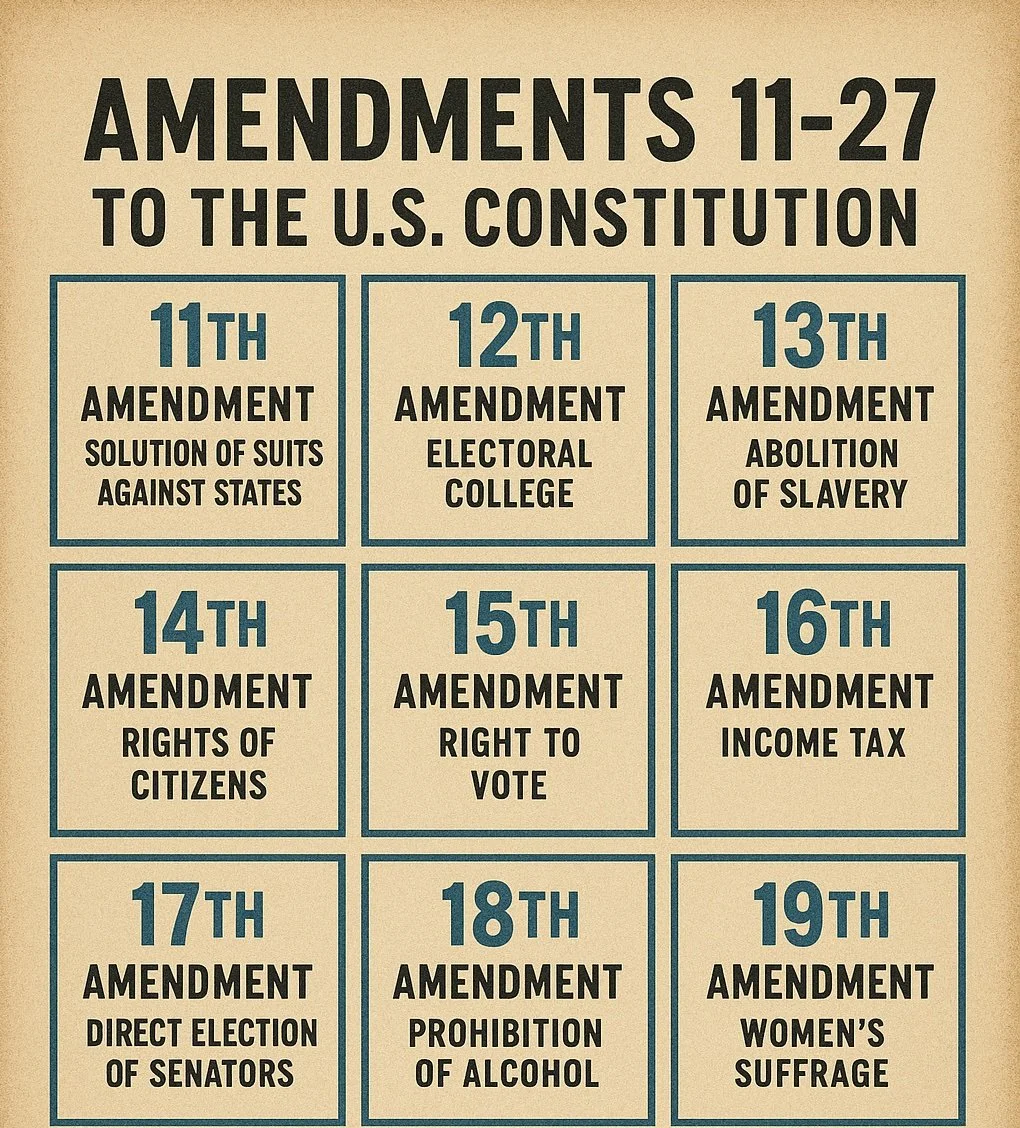

Amendments 11 thru 27 From 1795 - 1992

The constitutional amendments ratified after the Bill of Rights reflect a nation continually evolving. The most transformative are the post-Civil War amendments: the 13th abolished slavery, the 14th granted citizenship and equal protection, and the 15th secured voting rights for men regardless of race.

The Progressive Era brought major reforms, including the 16th amendment, which established a federal income tax, and the 17th, which allowed for the direct election of senators. The 19th amendment was a landmark victory, granting women the right to vote.

Other amendments have fine-tuned the mechanics of government, addressing presidential succession and term limits (20th, 22nd, 25th). The remaining amendments expanded democracy by extending voting rights to Washington D.C. residents and 18-year-olds, and eliminating poll taxes.