As Little as ‘Freakin’ Possible

-

![Destroyed city block]()

In case of emergency ...

The 19th-century Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote one of the most important axioms of statecraft: "War is the continuation of politics by other means."

His point is that military action is not chaos for its own sake. It is a tool of the state, a violent and final extension of political will, intended to achieve a specific political goal that diplomacy could not.

This profound truth has two critical implications—one for our leaders and one for our citizens.

First - It defines the ultimate responsibility of our political leaders. If politics is the art of running a state, then resorting to military force represents a failure of all other means. When leaders call on young men and women to fight and die, it is the gravest admission that statecraft has failed, more to the point, that the politicians have failed.

This is clear when facing a hostile foreign power. But what happens when leaders apply the language of war to their domestic rivals? When they describe a fellow American political party as an "enemy" to be "destroyed,” this is a complete failure of their elected purpose. They were elected to govern with their rivals, not to conquer them.

Second - This truth exposes the danger of a disengaged public. In the last presidential election, 89 million eligible Americans did not vote. Many who do vote claim they "don't care about politics."

Since the American Revolution, over 1.3 million American service members have died in war.They were sent to the battlefield by politicians. Because war is an extension of politics, you cannot separate the two.

To declare you "don't care about politics" is to declare you don't care about the very process that sends service members into harm's way. It is an abdication of your oversight. It means you are handing a blank check to political leaders—most of whom have never served—to make the most consequential decision a nation can make.

As combat veterans of multiple wars, we find this disconnect staggering. It is, of course, every citizen's right to ignore the political process. But we must be honest that this indifference has a cost. And for all too many, the cost is... high.

-

![Soldiers on building steps]()

The Role of the United States Military

There’s a stark phrase often used in military circles to describe the ultimate purpose of the armed forces: to kill people and break things. To put a finer point on it, the goal is to maintain a capacity for violence so absolute that it deters any adversary from threatening the interests of the United States. It is the credible threat of overwhelming force that keeps the peace.

However, that force has a specific vector: outward. The idea of turning it inward against the American people is antithetical to the soul of the institution. It is a concept that repulses service members, as it violates every principle of our training and our oath to the Constitution. This is not simply a cultural norm; it is a legal firewall. Federal law, with very few and extraordinary exceptions, expressly forbids using the military as a domestic police force. Doing so is not only illegal and counterproductive—it is an unforgivable breach of faith with the citizens we serve.

-

![JFK's Cabinet]()

Civilian Control

The role of the armed forces in domestic politics is strictly limited by law and foundational democratic principles. The core tenet is civilian control of the military, ensuring that the nation's armed forces remain a politically neutral instrument of the state, subordinate to elected officials, and are not used to enforce domestic laws or interfere in political matters.

This principle is balanced by constitutional and statutory exceptions that allow for the domestic use of the military ONLY in extraordinary circumstances. The legal framework primarily revolves around two key acts: the Posse Comitatus Act and the Insurrection Act.

-

![Military 'NOT' involved in civilian law enforcement]()

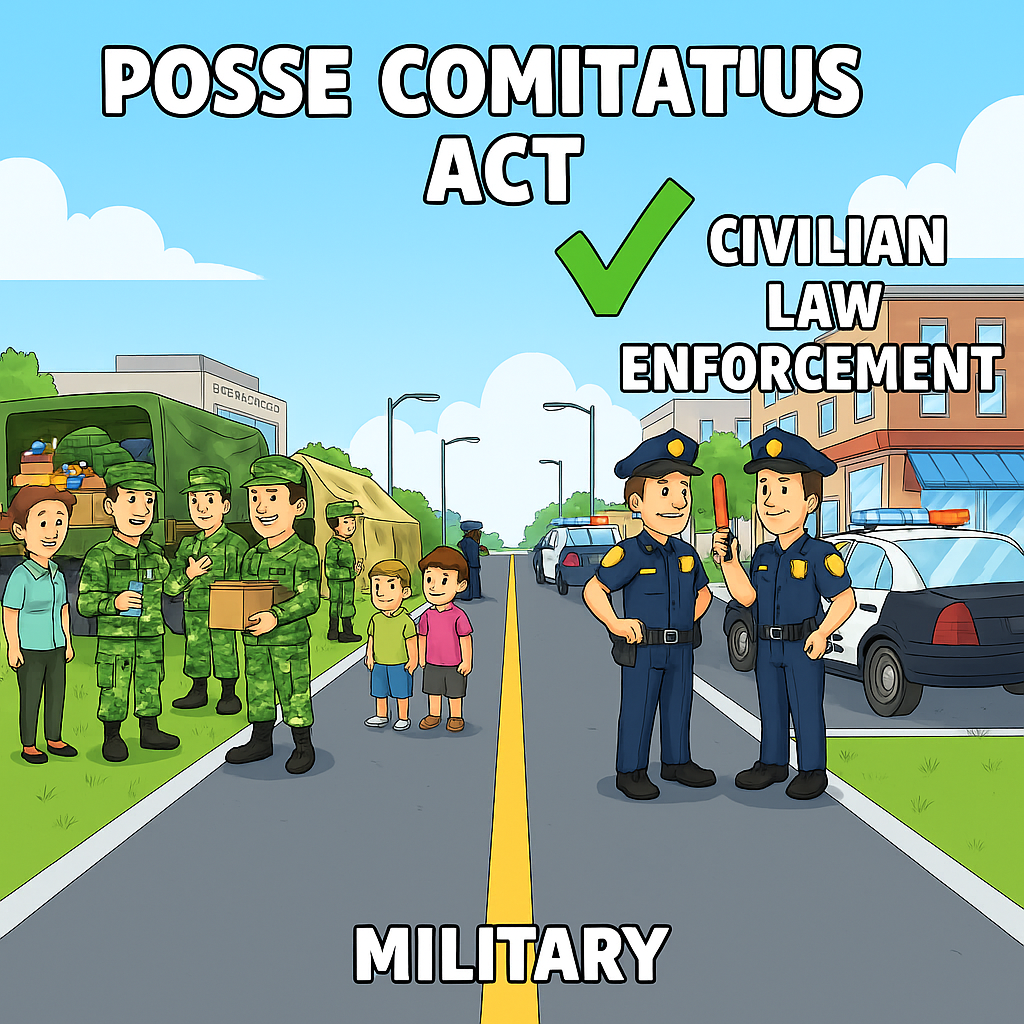

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 is the primary federal law that restricts the use of the active-duty military (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force) for domestic law enforcement purposes. The name "Posse Comitatus" is a Latin term meaning "power of the county," referring to the historical practice of sheriffs calling upon able-bodied citizens to help enforce the law.

In essence, the act makes it a felony to willfully use any part of the active-duty military to "execute the laws" unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or an act of Congress. This prevents the President or other officials from using the military as a domestic police force, a practice the nation's founders viewed as a significant threat to liberty.

This restriction does not generally apply to:

- The U.S. Coast Guard, which has a specific maritime law enforcement mission.

-The National Guard when operating under the command of a state governor (known as Title 32 or State Active Duty status).

-

The Insurrection Act of 1807

The Insurrection Act of 1807 provides the main statutory exception to the Posse Comitatus Act. It grants the President the authority to deploy active-duty military and federalize the National Guard to respond to crises within the United States. Invoking the Insurrection Act is a rare and significant event.

The President can deploy troops domestically under the following conditions:

- At the request of a state's legislature or governor to suppress an insurrection within that state.

- To enforce federal laws or suppress a rebellion against the U.S. government.

- To protect the constitutional rights of citizens when state authorities are unable or unwilling to do so. This provision was critical during the Civil Rights Movement.

-

The National Guard

The National Guard occupies a unique position as it serves both state and federal governments. This dual role is crucial to understanding its function in domestic operations.

State Control: In its most common domestic role, the National Guard is commanded by the governor of its respective state. In this capacity (State Active Duty or Title 32 status), Guard members are not bound by the Posse Comitatus Act and can perform law enforcement functions, such as crowd control or security, as directed by the governor. They are frequently deployed to respond to natural disasters like hurricanes and floods, as well as civil disturbances.

Federal Control: The President can "federalize" a state's National Guard, placing it under federal command (Title 10 status). Once federalized, Guard members are subject to the same restrictions as the active-duty military, including the Posse Comitatus Act, unless their deployment is authorized under an exception like the Insurrection Act